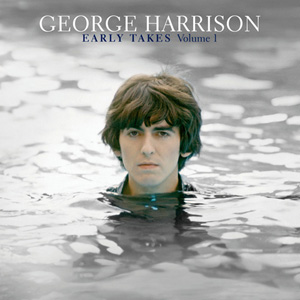

Artista: George Harrison

Álbum: Early Takes: Volume 1

Año: 2012

Género: rock

Duración: 30:27

Nacionalidad: Inglaterra

Año: 2012

Género: rock

Duración: 30:27

Nacionalidad: Inglaterra

Lista de Temas:

1. My Sweet Lord

2. Run of the Mill

3. I'd Have You Anytime

4. Momma You've Been on My Mind

5. Let It Be Me

6. Woman Don't You Cry For Me

7. Awaiting On You All

8. Behind That Locked Door

9. All Things Must Pass

10. The Light That Has Lighted The World

1. My Sweet Lord

2. Run of the Mill

3. I'd Have You Anytime

4. Momma You've Been on My Mind

5. Let It Be Me

6. Woman Don't You Cry For Me

7. Awaiting On You All

8. Behind That Locked Door

9. All Things Must Pass

10. The Light That Has Lighted The World

Alineación:

- George Harrison / guitarra, voz

En realidad, no estoy muy segura de quiénes son los que tocan. Teniendo en cuenta las versiones originales, deberían ser:

- Klaus Voormann /bajo (1),(3),(7), (9)

- Ringo Starr / batería (1), (9)

- Eric Clapton / guitarra eléctrica (3), (7)

- Alan White / batería (3)

- Jim Gordon / batería (7)

- Pete Drake / pedal steel (8)

- George Harrison / guitarra, voz

En realidad, no estoy muy segura de quiénes son los que tocan. Teniendo en cuenta las versiones originales, deberían ser:

- Klaus Voormann /bajo (1),(3),(7), (9)

- Ringo Starr / batería (1), (9)

- Eric Clapton / guitarra eléctrica (3), (7)

- Alan White / batería (3)

- Jim Gordon / batería (7)

- Pete Drake / pedal steel (8)

Acá venimos con otro disco del gran George! En este caso, se trata de un álbum que, como bien lo dice el nombre, nos trae excelentes demos y tomas alternativas de canciones pertenecientes a All Things Must Pass, Living In The Material World y Thirty Three & 1/3. Además, también incluye algunas versiones suyas de temas de Bob Dylan y Gilbert Bécaud y Pierre Delanoë. Dicho sea de paso, originalmente formaba parte de una edición deluxe en Blu Ray del documental de Martin Scorsese George Harrison: Living In The Material World.

La mayor parte de las canciones son de All Things Must Pass. El disco comienza con “My Sweet Lord”, aquel famoso tema que George escribió como una alabanza a Krishna, que también tenía como intención hacer un llamado para abandonar el sectarismo religioso. De hecho, él mismo aclaró que su intención, al mezclar el “Aleluya” con el “Hare Krishna”, fue la de demostrar que esas dos frases significan exactamente lo mismo. Pero creo que ya me fui un poco de tema. Volviendo al disco, continuamos con una lindísima versión de “Run Of The Mill”. También tenemos una de las primeras versiones de “I’d Have You Anytime” (coescrita con Bob Dylan), “Behind That Locked Door”, “Awaiting On You All” y la magnífica “All Things Must Pass”.

Como había mencionado, hay una interesante versión de “Momma You’ve Been On My Mind” (del buen amigo Bob) y de “Let It Be Me” (originalmente escrita por Gilbert Bécaud y Pierre Delanoë, y muy popularizada luego por The Everly Brothers).

De Living In The Material World y Thirty Three & 1/3 aparecen “The Light That Has Lighted The World” y una fantástica versión acústica de “Woman Don’t You Cry For Me”, respectivamente.

Estamos ante algunas de las tantísimas canciones hermosas, profundas y muy originales de George pero al desnudo, realzando aún más la belleza que éstas guardan.

Si sos fan de los Beatles o de George, ni dudes en llevártelo. Está imperdible!!

Gracias a la persona que lo compartió! (otra vez desconozco quién fue)

Y dejo por acá un par de comentarios más:

"George, in a photo taken in a Bahamian pool during the filming of Help!, holds his head above the water’s crystal surface, his face the perfect expression of the solemn young seeker braving the eddies and tidepools of the material world: a Siddhartha for the ‘60s. The image is rich, quiet, suggestive, like George at his best.It’s beautiful wrapping on a gift that isn’t quite there. Olivia Harrison, Giles Martin, and whomever else was involved have made this a tender little release, but behind the front cover Early Takes: Volume 1 holds little in the way of context, data, or style. It needs more imagination, in all aspects of its presentation—titling, annotation, programming. Modest to a fault, the album is barely over a half-hour long, with a number of songs which, due to their tentative, exploratory nature, do not resolve in worked-out endings but simply stumble to stopping points before dissolving behind giggles and talk. There’s no sense that the selections have been sequenced in a particular order for ebb and flow, startling starts or dramatic culminations. Granted, it’s a collection of demos, sketches, and, indeed, “early takes”; but those who assembled it were hardly obliged to make the album sound like an early take of itself.It’s to my surprise, I will say, that few of the tracks are among those which have been commonly available on bootlegs for well over a decade—chiefly, but not only, Beware of ABKCO! and Songs for Patti, both released in 1994 on the Strawberry label. Nor are most of these tracks found even on the five-disc The Art of Dying: The Complete All Things Must Pass Demos, Sessions and Remixes. But astonishingly for a collection devoted to a man who spent so much of his life in the proud community of session players, the liner offers no information on accompanying musicians or recording dates. That’s all given, no doubt, with the deluxe DVD, but it’s a real skimp not to provide it here: I paid my $12—give me the names.Track by track: 1. “My Sweet Lord.” Previously unheard by me, this is listed as a demo, though an engineer slates it “Take 1,” and George’s ill-tuned acoustic guitar is accompanied by drums, presumably Ringo’s, and bass, presumably Klaus Voormann’s. The run-through is ragged, sketchy, the merest shadow of the resultant glory.2. “Run of the Mill (Demo).” Again slated as Take 1. George solos on acoustic. This is the same demo that’s found on ABKCO! and Patti.3. “I’d Have You Any Time [sic] (Early Take).” Such a gorgeous song. This full-band version of the Harrison-Dylan composition, very similar to the released take, features some bum notes from Clapton, but it has a charging, forceful quality on the refrain that the LP version lacks. Includes a count-in, for what it’s worth. (A lot: I love count-ins.)4. “Mama You’ve Been on My Mind (Demo).” Another previously unheard outtake. George’s execution of one of Bob Dylan’s most affecting early ballads is expectedly sweet, with some haunting instrument (what instrument?) tootling in the background. Sounding quite finished for a demo, it could have been released commercially—though clearly it would have violated the Wagnerian gestalt of All Things Must Pass.5. “Let it Be Me (Demo).” Another pretty, unbootlegged cover version, this time of the Everlys, with some trademark Harrison guitar flourishes. (Who is the harmony vocalist? George O’Hara Smith? Drat the lack of info!) This too sounds well beyond the demo stage. Note that Dylan included a terrible version of the same song on hisSelf-Portrait album, released back at the beginning of 1970.6. “Woman Don’t You Cry for Me (Early Take).” The Dylan theme continues; clearly George, unlike John, believes in Zimmerman. This is a 1963-reminiscent folkie thing whose chief pleasures are a nice acrobatic vocal and some tricky folk guitar—we don’t often hear George working out on acoustic this way. Someone pops a Jew’s harp to the rear. (Who?!?)7. “Awaiting on You All (Early Take).” A small-band fuzz-funk version of the enjoyably bombastic, traffic-jam album version. [Mis]announced by George as “Awaitingfor You All.” Previously unheard.8. “Behind That Locked Door (Demo).” George flies solo, until a steel guitar (Pete Drake?) unexpectedly steals in for a lovely liquid interlude, to lift yet another of these “early takes” past demo status. Refreshing, and quite lovely in its simplicity; might be superior to the album version. Previously unheard.9. “All Things Must Pass (Demo).” Acoustic guitar, bass, drums, and a little dull. Lacking the focused, fixated quality of the one-man, one-guitar Anthology 3 demo, it stutters to a premature close.10. “The Light That Lighted the World (Demo).” Prettily done, but a weak closer. The only song to come from Living in the Material World, and probably meant as a teaser-pointer to Volume 2.In all, Early Takes: Volume 1 is a fine collection that rates with the better All Things-era bootlegs. The preponderance of unbooted material lends it value and novelty, but the complete presentation, as noted, is lacking in almost every department. From a bootlegger, such deficiencies would be excusable; from intimates and insiders with unfettered access to the Harrison vaults, they are frustrating and unaccountable.Perhaps this is a kind of placeholder release, designed, in the fashion of operating systems or refrigerators, to be superseded somewhere down the line—perhaps by a time-spanning, multi-volume outtakes collection loaded with the meat and potatoes of information and the garnish of graphic design. But if that’s the plan, it’s foolish and frustrating. Each segment of a staggered release ought to wear its own colors, have its own personality, be a satisfying immersion in its own piece of time. Each of theBeatles Anthology CD installments was awesome on its own, while still fitting into a clear overall design. Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series—whose Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (1969–1971), released last August, included a number of Dylan-Harrison collaborations from the Early Takes era—is a model of how such releases should be done; yet another is Neil Young’s mammoth ongoing Archives series.But on second thought, forget the “placeholder” theory. I think the more likely, and even more perplexing, explanation is that no one in the Harrison orbit saw Early Takes: Volume 1 as a particularly important release—that it was felt to be, at best, an appendage to the Living in the Material World documentary, with cultural muscle for both coming courtesy of Martin Scorsese and HBO, more than George himself. But the man and his songs deserved better than this near-nonentity of a collection, which is, after all—aside from the bonus track-rich thirtieth-anniversary edition ofAll Things Must Pass—the first official issue of unheard Harrison material."

Devin McKinney

"It’s been nearly 11 years since we lost George Harrison to cancer, yet it feels as if we’ve been living without him for much longer. Over the last decade and a half of his life Harrison spent far more time tending to the sprawling gardens (which, it should be noted, cover an area the size of a small town) than he did recording music. A reflective, deeply spiritual man for whom the daily grind of a working musician’s life held no allure, Harrison was determined to live according to his own rules. While he never officially retired, in his later years he seemed to have found an inner peace from his non-musical pursuits that he never would’ve found schlepping around the world with a guitar in his hand.Save for one final studio album and a couple of remasters, the posthumous career of the Quiet Beatle has also been pretty quiet. Unlike other grossly mismanaged estates (looking your way, Courtney Love) the guardians of Harrison’s music and likeness, widow Olivia and son Dahni, appear to be determined to protect and honor the legacy of a man who lived with a lot of dignity. Rather than cobble together some rush-job documentary, the Harrisons allowed themselves time to grieve and then went out and hired one of the world’s greatest living filmmakers, Mr. Martin Scorsese, to bring George’s complicated life story to the big screen. Scorsese and his team spent several years piecing together Living in the Material World, a moving yet occasionally exhausting documentary that should stand as the final word on the journey of George Harrison. Arriving with little fanfare in conjunction with the domestic release of Scorsese’s film is Early Takes, Vol. 1, a seemingly random collection of demos from the early 1970s that makes for a thoroughly satisfying listen despite its brief running time. Not all of these mostly acoustic sketches appear in the documentary, and there isn’t a shred of information about when this music was recorded and who’s playing on it. We have to rely on what we already know as fact to piece together a narrative. By the time The Beatles split up in 1970, Harrison was sitting on a wealth of material, much of which had been, for reasons far beyond this reviewer, denied placement on the last few Beatles albums. While Paul McCartney released the pastoral McCartney and John Lennon purged his soul onPlastic Ono Band, Harrison linked up with Phil Spector for All Things Must Pass, a towering triple LP that’s widely considered to be the greatest solo album released by a Beatle. More than half of the songs on Early Takes, Vol. 1 are All Things Must Pass-era demos. Pulled away from the shadow cast by Spector’s mighty wall of sound, the beauty at the core of Harrison’s compositions is allowed to shine through.Much credit is due to Giles Martin, son of legendary Beatles producer George Martin, who has meticulously restored Harrison’s original recordings. At no point do these songs sound like demos that were recorded over 40 years ago, due in no small part to the strength of Harrison’s performances. We’ve rarely heard Harrison sing better than he does here. Tracks like “Run of the Mill” and “Behind That Locked Door” are one-take run-throughs, yet they’re flawlessly executed. More fully formed are covers of Bob Dylan’s “Mama, You Been on my Mind” and The Everly Brothers’ “Let It Be Me”, the latter of which features some impossibly gorgeous self-harmonizing from Harrison. Hearing Harrison in such an intimate setting is a revelation and it makes one wonder why he rarely worked in this format throughout his solo career. Not to take anything away from his work with Phil Spector or Jeff Lynne, but it’s a shame that, more often than not, Harrison’s gentle voice and aching melodies were overwhelmed by production. It’s a pair of full-band demos that provide the missing link between All Things Must Pass and Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band. Before Spector showed up with his army of session musicians, horn players, and gospel singers, Harrison was working on something that sounded every bit as raw as Lennon’s album. Of course, Harrison is using the same rhythm section of bassist Klaus Voorman and drummer Ringo Starr (Note: there’s nothing in the liner notes to confirm this but I’ll be damned if that isn’t Ringo behind the kit). Ringo, who never played better than he did in 1970, gives “My Sweet Lord” a laid back, vaguely bluesy feel and then goes absolutely apeshit on a blistering work-up of “Awaiting on You All”. The only indication that this track, with its crunchy guitars and backwards drum fills, wasn’t pulled from thePlastic Ono Band sessions is Harrison’s voice.Both The Beatles and John Lennon have been anthologized, and those projects, while comprehensive and informative, are a bit of a chore to sift through. George Harrison’s Early Takes, Vol. 1, on the other hand, practically demands to be listened to on repeat. Rather than throwing open the vaults and inundating us with a deluge material, the Harrison family has made a wise choice in rolling out one slim volume at a time. Hopefully we’ll continue to be reunited with Harrison’s gentle spirit through these archival releases for many years to come."

Daniel Tebo

Comments

Post a Comment